Treasures Untold, Pt 2.

- Bob Bell

- May 31, 2025

- 23 min read

Updated: Aug 30, 2025

A MODERN 78RPM READER

THE LUST FOR SHELLAC: Confessions of an addict, Part 2.

My good friend Josh Rosenthal who heads Tompkins Square Records out of San Francisco, recently published a fascinating book on 78 rpm records, the book being a collection of essays by collectors on the joys, perils and caveats on the condition - the condition being both that of the records in question and that of the mindsets of those involved.

The writers include Josh himself, 15 year old Jay Burnett, John Heneghan, David Katznelson, Dick Spottswood - technically an interview, Joe Lauro and others, including yours truly.

It is a limited edition, available at record stores for Record Store Day. Check with your local record store to see if they have a copy.

The book also comes with a CD of old-timey tunes associated with the era. Yes, I know what you are thinking. A CD? Why not a real old-time 78 album? Well, in a word, economics. Think about it.

To give you a little taste of the written contents, the second half of my contribution follows.

The first half can be read here: https://www.78crazy.com/post/treasures-untold

THE LUST FOR SHELLAC: Confessions of an addict, Part 2.

So, 78s have had this very odd attraction for me … this Smiley Lewis saga was

repeated, albeit in a different guise, over a decade later, on the day I was leaving

London to travel to the US.

I had been back working at Island for a few months in the winter of 1979, and was

leaving the city in February of 1980. Having called in at their offices to say my last

goodbyes, I was walking through Hammersmith to catch the bus to the airport when I

passed a middle-aged woman clutching a 78. I could see she was a bit overweight,

dressed rather shabbily, her hair was obviously bleached, but these details were nothing

compared to the importance of the record she was holding. “Blue Moon” by Lynn Hope.

On Aladdin. Right here in Hammersmith, this very day, this very moment. I approached, looking at the record. “You wanna buy it, luv? Twenty-five pee?”

What strange serendipity.

An Aladdin, for sale, at a bargain price, twenty-five pence, from this odd woman, who had just this one record. How far had she walked, hoping to sell this one disc? The two of us stood there, looking at each other. Pedestrians walked by, oblivious to the very remarkable fact that Lynn Hope was in Hammersmith that day. I imagine that I was probably the only person on the streets of London that day who would have been tempted by a Lynn Hope 78 on Aladdin. Indeed, how many pedestrians would have even heard of Lynn Hope, let alone coveted a fragile twenty-

five-year-old recording by him?

Undeterred by the fact that I was on my way to America and could not possibly take it

with me, I bought the record. This meant a fast and panicked detour to my friend’s

house in Clapham where I had been staying, in order to stash the record, and then an

even more panicked rush to the airport where I miraculously caught the plane to New

York.

My trip to the States was prompted by the break-up of a relationship, and the urge to do

something that had been a long-occurring dream: to roam the highways and byways of

the USA, with vague ideas of looking for the ghosts of Jack Kerouac and Blind Lemon

Jefferson, with an ear open to catch the sound of saxophones in the American night.

I won’t go into all the details of that mad summer, other than to say I spent a wonderful

few days in Atlanta, Georgia, staying with the gloriously named Deveraux McClatchey

IV, who managed Piano Red, and while in Atlanta, I met up with the nine-piece Roomful

of Blues, with whom I later worked for over twenty years. I then spent an unforgettable

six weeks in New Orleans, after which I set out hitchhiking around the Western states,

ending up in Mill Valley, a few miles north of San Francisco, staying with Danny

Carnahan and Robin Petrie, two musician friends.

Now, when I had been in New Orleans, I had visited a handful of record stores,

but being mindful of my vagabond status, had not bought any records. I obviously had

nothing to play them on, nowhere to keep them, and hitchhiking with an armful of

records was simply out of the question.

But in Mill Valley the situation changed, rather radically. At supper one evening, Dan or

Robin mentioned Village Music, a record store in town that they said had the most

wonderful stock of records of all genres, new and used, and that they just knew I’d get a

big kick out of visiting it.

The next morning, I caught a bus into town and happily found it stopped outside the

store. My hosts were right—it was more than a store—it was an emporium in every

sense of the word. The walls were covered in vintage posters from blues, jazz, R&B,

and rock ’n’ roll shows from the ’40s through the ’60s. Louis Jordan, Percy Mayfield, Big

Jay McNeely, Johnny Otis, Lowell Fulson, B. B. King, Pee Wee Crayton, Joe Houston,

T-Bone Walker, Fats Domino, Count Basie, Big Joe Turner … a visual history of the

music I loved.

Rows upon rows of LPs took up the main floor space while one corner

was reserved for shelves and boxes of 45s, and, lo and behold, a separate room at the

rear was filled with 78s, shelved in rows from floor to ceiling.

As I entered the 78 room, a strange calm came over me, a slow fuzzy feeling of warmth.

It was almost as if I was up on high watching myself below, an out-of-the-body

experience. Initially, I pulled records from the shelves at random, just checking the

organization, the pricing, the condition. Indeed, they were categorized to a large extent

—jazz in one place, R&B in the next, then country, and so on. Within twenty minutes, I

realized I needed to be more methodical and started at the logical beginning, the first

shelves by the door, which happily housed the R&B section.

This was the motherlode. Not just a few records, not just a few dozen records, not just a

few hundred records—but 78s by the thousands. Oh my god, the labels! Percy Mayfield

on yellow and black Specialty, then Roy Milton on a red Specialty, and then, look,

Camille Howard on a black Specialty, but with much older artwork. Modern labels

abounded, together with original Modern Music (with the little musical score on the

label), Imperial, Cash, Money, Recorded in Hollywood, Dolphin’s, Savoy, King, Aladdin,

Score, Fortune, Chess, Parrot, DeLuxe, RPM, Intro, DC, Comet, Exclusive, Excelsior,

Down Beat, Swing Beat, Combo… Many of these labels I had heard about through

Blues Unlimited and other magazines, but there were many, many more that were new

to me, ones I discovered were local labels, such as Cava-Tone, Scotty’s Radio, Big

Town, Down Town, Rhythm… And here they were in front of me, three-dimensional and

real!

As the hours passed by, my sense of calm was overtaken by a frenzied urgency, an

acknowledged need to go through all these shelves as the clock ticked, and without

consciously realizing it, I was putting aside copies, making a pile in one corner of the

room. I mean, just look at the prices! twenty-five cents, forty cents, fifty cents, seventy-

five cents, here a dollar, sometimes two dollars, but, in the main, the records were under

a dollar. Sure, some of them were a bit whipped, but the one thing that I had learned

over the years was that a shellac 78—and here is the rub—although more brittle than a

45, would actually take more abuse than a vinyl 45. In other words, these 10-inch

repositories of music really played and sounded better than their modern counterparts,

regardless of scratches and blemishes. Exactly why this should be so, I can only

suggest that, as the groove is deeper and wider, there is more room for the music.

Regardless of the reason, the fact remained that here in this room was an unparalleled

trove of American musical history, far too much to be absorbed by simply looking at the

labels, as much fun as that was, and I knew I would kick myself forever if I didn’t plan for

future research by amassing a stash.

Regardless of the reason, the fact remained that here in this room was an unparalleled

trove of American musical history, far too much to be absorbed by simply looking at the

labels, as much fun as that was, and I knew I would kick myself forever if I didn’t plan for

future research by amassing a stash.

And so my pile grew.

And grew.

The hours passed in a blur. Possibly I stopped once or twice to visit the bathroom, but

the idea of lunch never occurred. Finally, around 4:30 in the afternoon, I arrived at the

end of the last shelf and pulled the last record. Whether it was a keeper or not, I am

afraid I cannot remember. However, I do remember making two trips to the cash register

to have my haul rung up. The owner, John Goddard, whom I would get to know years

later during visits to the store while out on tour with Roomful of Blues—he would open

the store for us at 2 a.m. after a show in San Francisco—grinned as he totted up the

records and put them in boxes. “You’re probably going to need a handcart to move

these,” he said.

Indeed. It took two trips to carry the boxes outside to the bus stop. I blinked in the glare

of the afternoon California sun. Traffic swept by, and finally, the bus came. The driver

patiently waited as I loaded my boxes, sweating and grunting. Sitting there as the bus

pulled away, I came to grips with the reality of the situation. What had just happened? I

had just purchased over two hundred 78s weighing close to a hundred pounds, more

than I could comfortably carry, and I was hitchhiking. What had come over me? Why

had I suddenly succumbed to what had been a bout of undeniable madness, six hours

of irrational mania, a mania prompted just by the sight—yes, just the sight—of these old

records? Had I even listened to any of them? No. Had I really any honest idea of how

good they were? No. Did I even know who some of the artists were? No.

What the hell just happened? Deep inside, I knew. It was the same fever that had come

over me with that Smiley Lewis record, and the Lynn Hope record.

I had simply succumbed to a power greater than I. Oh, to be sure I could swallow the

bromides of “researching American musical history,” but that wasn’t really the case, that

wasn’t what had just happened. What had happened was that I had become

overwhelmed by a collector’s frenzy, a mania, a passion, a mad and blinding need to

own and possess a huge bunch of aging and scratched records that I had no means of

carrying, storing, or transporting anywhere.

I was stuck in the deep and sticky center of a collector’s pickle, which was

resolved thus: A few days later, I took a bus to Seattle, where I stashed the records in a

locker at the bus station and went on to Point Roberts to stay with a friend I had met a

few weeks earlier. She was English and was returning to England in a couple of weeks,

so I gave her the key to the locker, and she very kindly, and at great risk to her back,

took the records back with her to London. A couple of months later, after I returned to

England, I met up with her and retrieved them. A few months after that, I moved to

Rhode Island and had the records shipped there. (Twenty-two years later, in 2002, I moved to

Oakland, California, and so now those records are back where they started).

By 1981, I had moved to Rhode Island to work with Roomful of Blues, with whom I wore

many hats: publicist, driver, sound engineer, and eventually manager. Traveling with the

band extended endless opportunities for hitting junk stores and, naturally, I took full

advantage. We worked the eastern seaboard a lot during the ’80s, and the Richmond,

Virginia, area proved to be exceptionally fertile ground. Each trip, I would return with

Buddy Johnsons on Decca and Mercury, Brownie McGhee on Alert, Tiny Bradshaws

and Wynonie Harrises galore.

I had read stories of the Buddy Johnson band playing dances in tobacco warehouses, flatbed trucks serving as stages, and would look at the records scored on those trips and wonder about the provenance of them. Just who had originally bought them? Was it just after one of those dances, with a head full of joy after the weekend’s fling, that the original buyer had walked into a record shop after work the following Monday and purchased that copy of “Please, Mister Johnson”?

Had they taken it home, wound up the Victrola, and then dreamily danced around the living room? Or, maybe they had graduated from the spring-driven machine and played their discs on an RCA tabletop player, using the radio as an amplifier? All useless conjecture, but, nevertheless, almost as entertaining as listening to the records themselves.

On one visit to Richmond—this was during the 90s and the CD era—we had a day off, and I wandered away from the hotel and found a big indoor flea market held inside what had once been a supermarket. Dozens of tables, mostly covered with bric-a-brac, used clothing, books, kitchen appliances, but a few records here and there. The thing with junking is that you have to look. Most folks are not out looking for 78s, and so they are

rarely sitting on top of a table in the prime selling space. More likely, they are at the

bottom of a box, behind other boxes, lonely, forgotten, and anonymous. After an hour

spent poking around this cavernous place, I was just about to give up, when I spied a

dusty cardboard box under a table, almost hidden under a pile of rags. Getting down

onto my knees—and God only knows how much time we collectors spend on our knees

—I pushed aside the rags and found myself looking at a Paramount. Blind Lemon

Jefferson’s “One Dime Blues.” And then a Joshua White on Perfect. Then another

Perfect, this time Buddy Moss. Sleepy John Estes on Decca. There were around sixty blues

records in that box and about fifty were pre-war blues.

I bought the lot, for about a buck apiece. That same trip, I bought a CD—I forget

who it was—and when I got home, excitedly played everything. All the 78s played fine

with no skips apart from one of the Blind Lemons—there had been two different ones in

the box—which was cracked. Some were noisy, and a couple were really whipped, but

they all played. The CD was another story. It did that thing that bad CDs sometimes do

… I call it a “digital breakdown,” and it is most certainly not the kind of breakdown one

associates with rural instrumental music.

It is common these days to digitize music, and certainly it is easier to put on a playlist of

several hours of music than to play single records, whether they be 78s or 45s. The

downside is that the music becomes background music … one undertakes differing

tasks while the music is on, thus one’s attention wanders from the performance. I have

a large collection of CDs, all of which I have put into iTunes on my computer. I have a

couple of backup hard drives, but, nevertheless, every now and then I go to play

something, and it is not there—the file is blank or has been corrupted. True, I have kept

the CDs themselves, so I do have a reserve of “masters,” but even that system is not

infallible, as on occasion, a CD itself will prove to be a victim of digital breakdown.

Physical records, however, are another matter. Certainly, they can be broken or

mistreated, but by simply sitting on the shelf, they have a degree of permanence that is

Space is another consideration, however. I have no idea how many 78s I possess. I do

know that when I moved to California from Rhode Island I had to figure out the weight of

my collection in order to figure out what size truck to rent. To the best of my memory, the

total weight over twenty years ago was in the range of three or four tons, and it must

have doubled since then. Fortunately, for the structural integrity of the house, they are in

the basement. So, they undeniably take up a lot of space, while the music, I imagine,

could fit on a few thumb drives. So, there is that.

However, I think of my 78s as being masters too, and if treated kindly, they can be hard

copies of what I might have in iTunes—although I think I possess probably only around

fifteen percent of them in digital form.

Of course, they can only act as masters if I don’t sell them...

On one trip to Texas, I scored a copy of Rabbit Foot Williams’s “I’m Gonna Cross the

River of Jordan Some o’ These Days”/“I Want to Be Like Jesus in My Heart” on

Silvertone. It was the only 78 in a booth at a flea market, and I think I got it for about

four dollars. I had no idea who he was, but undeterred by Two Ton Baker, he sounded

like a worthwhile gamble. Some years later, I read in 78 Quarterly that only three or four

copies of this record were known to exist. The piece also mentioned that Mr. Williams

was, in fact, Sam Collins. Taxes were due, so I digitized it and put it on eBay, and it sold

for a very large amount of money. As I wrote this, I looked for the file, but could only find

one side of the record, and that one didn’t sound too good. The moral being that a 78 is

a more reliable long-term storage medium than a digital one. Until taxes get in the way,

that is.

The Southwest was always fun to travel to—Fort Worth, Dallas, Houston, Austin… I

remember walking into a store close to the Capitol in Austin that sold nothing but 78s.

Imagine that, on the street leading to the Texas State Capitol, a store that sold nothing

but 78s. This was in 1981 or 1982! Unsurprisingly, on the next trip, it was gone.

San Antonio was another good hunting ground…loads of pre-war blues and

plenty of western swing too.

Kansas City made for a good visit…the Music Exchange was a very cool store,

with rows of shelves of 78s behind the counter. After a couple of visits, I was accorded

the great honor of being allowed to wander unaccompanied in this inner sanctum, a

treat I took advantage of on every subsequent visit.

The years I spent living in Rhode Island proved fruitful … there were several stores and

flea markets where one might find records. While visiting one in nearby Connecticut, I

got to talking to someone who mentioned a warehouse in Providence that had an entire

floor of 78s, piles of them, sitting upon pallets. I scribbled down the address and visited

there the following day. The place was a huge former mill-come-factory whose

manufacturing days were long gone and was now being used as a storage facility, run

by two brothers who roamed the buildings and pathways on electric golf carts,

communicating on walkie-talkies. Smoking constantly, both wore polyester tracksuits

although neither looked as if they ever actually exercised, They were suspicious and

humorless, but did acknowledge, that, yes, they had a certain number of records in one

of the buildings, and just, what, exactly was my interest? Ten minutes or so of verbal

jousting ensued, as positions were assumed, probed, examined, and considered. I took

the part of the interested collector who possibly might take the lot off their hands, and

they, custodians of a large stash of a product of which they had no knowledge, but

obviously and desperately wishing to maximize its value, about which they, like me at

that point, had not the faintest idea. It became rapidly obvious to both parties that the

records in question needed to be examined before any further discussions were

possible.

They led me to one of the buildings. The two of them astride a golf cart each, and I

briskly stepping behind them, feeling I was following Tweedledum and Tweedledee. We

entered through a pair of large wooden doors, covered in fading and flaking paint, and

which opened with creaking hinges. I was beginning to feel as if I were on a Hammer

Studios film set.

There, sitting upon row upon row of wooden pallets, which I quickly totaled to be about

55, were boxes and boxes and boxes of brand-new 78s. This was a stash beyond my

wildest dreams. It transpired that the records had been owned by someone who had

rented the space to store them, and who had then fallen behind in the rent. And the two

brothers had assumed ownership of the records in lieu of rent owed. God only knows

how many records there were there. The average pallet measures something like 40 inches

by 48. So, each pallet had several layers of four 10-inch boxes by four 10-inch boxes.

16 boxes per layer, each containing 25 records, 400 records per layer. And the boxes

were stacked five, six, seven, perhaps eight high. Assuming an average of seven high,

that came to around 2,800 records per pallet. Multiplying that by 55 meant that there

were around 154,000 78s sitting on that warehouse floor. All brand new, mint, unplayed

… no matter what grading system one used, they were MINT. Not M-, not N-. No sirree

… these babies were undeniably MINT.

I tried not to display any untoward enthusiasm. Approaching one pallet, I opened a few

boxes at random. A closed box promises many things—once opened that promise

dissolves into cold reality. Anticipation and discovery are funny things, the smiling hope

for the future that is followed by the realization of that shining future becoming the glum

present. Some of the boxes contained 25 copies of the same number, just as they had

been packed at the pressing plant. Others enclosed two, three, four or five differing

records on various labels. The vast majority were postwar pressings—most early ’50s—

which was grounds for optimism. Genres ranged from pop to jazz to a smattering of

blues and R&B, and the labels ranged from common black Deccas, red Columbias, and

orange and blue Corals to more intriguing imprints like Atlantic, Hub, Ruby, and

Commodore.

Tweedledum and Tweedledee were beginning to make impatient noises, and I realized

that I was in no position to propose a deal, if for no other reason than it would take a

couple of days to really assess what the value might be, and more pragmatically, I knew

two things the Tweedles did not.

I had no ready capital, and, perhaps even more importantly, nowhere to store such a

huge number of records. I proposed a meeting the following week, when I would return

with a colleague who had the experience of marketing old records in quantities, and

then together we could figure out a way forward that would hopefully satisfy one and all.

And thus, the following week I returned with Al Pavlow, known to collectors as Big Al,

although truth to be told, he was more Small-to-Medium Al. He lived by himself in

Providence, in a house filled with records. Every room, including the bathroom and

kitchen, had shelves sagging with records. He had been married decades before, but

it’s a safe bet that the true love in the house had ultimately been decided in favor of the

records. Al was a bottomless well of information about popular music, and his book, Big

Al Pavlow’s R&B Book is the definitive work on the popularity of the blues and R&B,

tracing as it does the year-by-year development of regional and national styles and

artists. Published by Music House Publications, it is well worth tracking down. Al and I

spent a very long day at the warehouse, happily left to our own devices by the two

brothers. As we delved into the pallets, it became apparent that they basically

comprised a giant mountain of schlock. To be sure, there certainly were desirable

records here and there, pleasing obscurities on equally obscure labels, but for every

record of interest, there were a couple of hundred that were not. Of course, there was

always the promise of the next pallet … that might be the one!

Our plan was to pull a couple of hundred records and ship them to a friend of Al’s who

regularly conducted 78 auctions and see whether we might develop this into a much

bigger monthly auction. We proposed this plan to the brothers, suggesting it as a kind of

club whereby they would store the product, we would market it and split the proceeds.

Tweedledee and Tweedledum hemmed and hawed … it wasn’t what they had hoped

for, but at that time it was the best option they had. Al and I departed with a couple of

hundred “samples” each, and a promise to be in touch in a week or two.

As always, life got in the way. I left the next day to go on the road with Roomful, and by

the time I got back two weeks later, the older and grimmer of the two brothers curtly told

me over the phone that the former owner had come up with the back rent and had

repossessed the records.

The postscript to this story is that I heard from several collectors over the ensuing years

that this collection had been well picked over before we had found it … it had been

picked clean of the Suns and Meteors and who knows what else. The final bookend to

this story came two or three years after Al and I had spent that day in that cavernous

space, and that was when the Providence Journal ran a series of stories detailing the

criminal activities of the brothers, and, to use the local parlance, they went down. I still find myself dreaming about those pallets, though.

In many ways, the joy of collecting has two sides: both As. There is the exhilaration of the hunt—the searching in out-of-the-way corners, rifling through boxes, the contented exhaustion one can enjoy after the physical labor of moving heavy objects in hot, dusty spaces results in successfully cornering a particularly elusive prey.

And then, there is the archaeological aspect, or perhaps it is better described as

anthropological. Whatever adjective you wish to apply, there is the undeniable joy of

holding a single-sided record from around 1900, maybe an Oxford, a Busy Bee, or

possibly a plain old Victor. Here is an artifact from over a century ago, a window into

time past. Look at the artwork—all the fancy filigree scrolls, the artist listed as Mr. or

Miss, or possibly no artist listed at all, maybe just Band. Who bought this record in 1903,

and just what pleasures did it bring forth? In what kind of gatherings was it played and

listened to? How many times was the fancy, new Victrola cranked, the ritual of changing

the steel needle observed? Did the listeners politely sit, or did they dance and frolic,

passing the claret and the sarsaparilla?

The tastes and styles of the day varied from military marches, opera, and like

fare for polite drawing-room entertainment to ragtime and minstrelsy to appallingly racist

tropes and vaudeville humor. And as the years passed, the first glimmerings of jazz and

dance bands, the orchestrated blues of Handy and Sweatman, Jim Europe, and the

cacophonous novelties of the Original Dixieland Jass Band, who were to jazz what the

Rolling Stones were to blues fifty years later. Not only are these artifacts to be held and

viewed, physical objects of a certain time, but they also possess the extra dimension of

sound, reproducing an event from decades or over a century ago, an event captured in

the groove … truly a record of what was then that can be experienced in the here and

now. It was a revolutionary concept.

And then there were the sizes—10-inch discs were the norm, but there were Little

Wonders at 5 1/2 inches, Victors at 7 inches, Pathés at 11 inches, and then those red

Victors and Victrolas at 12 inches. (Later, with the advent of radio, came the 16-inch

transcription discs). And the speeds—76, 78, 80, 82 rpm. It was a while before the

industry adopted a standard speed, so one has to wonder just how the ordinary punter

fared in the absence of a strobe to determine actual speed. To be sure, all the old hand-

cranked phonographs had a ‘fast/slow’ lever, thus it was up to the listener to decide

when the speed was correct. Hopefully, he or she had a discerning ear…

For me, these older records hold a certain fascination due to their age, and the fact that

they reflect the fashions and styles of bygone times, but these are intellectual musings

over recordings that, in the main, do not hold much, if any, artistic attraction for me. It is the

blues and jazz recordings from the ’20s through the ’50s that I personally love, and most

especially the last fifteen or twenty years of the 78 era, from the ’40s through the end of

the ’50s, at which time 78 production ceased in the US.

Apart from the above reasons and rationalizations of 78 collecting, there is a more

mysterious, potentially darker side, and that is—let us speak the truth—the addictive

side. For all the times that collectors joke about their love for old records as a disease, a

sickness, a compulsion, there is an undeniable grain of truth to these age-old jests. The

Mayo Clinic’s opening statement about hoarding disorder is as follows: “Hoarding

Disorder is an ongoing difficulty throwing away or parting with possessions because you

believe that you need to save them. You may experience distress at the thought of

getting rid of the items. You gradually keep or gather a huge number of items,

regardless of their actual value.”

We say we save aging records because we love the sounds in the groove, but

honestly, how many times do these records get pulled from the shelves and actually get

played? Oh, to be sure, the record was cleaned and played the first time it came home,

and perhaps once or twice more, but in most cases, and especially in a collection of

thousands or tens of thousands, the discs just sit there—testaments to a strange mania,

an obsession, a fierce and fervid fanaticism—tokens to our taste, our erudition, our

acumen, our knowledge, our interest, our passion, and that passion is … what? A

passion cloaked in an undeniable love of music and its history, but underlying it is an

unquenchable thirst to hunt, purchase, and accumulate. It’s all rather odd and, were it

not for the most astounding sounds that might be heard on rare occasions, possibly

rather pathetic.

And so now, in 2023, I am in my 78th year… Yes, pause a while and consider that

remarkable fact, that undeniable happenstance…in reaching the age of 78, which is 78

revolutions around the sun, and all of its remarkable and terrible significance, I have to

reflect on my possibly imminent mortality, my moving on to that Great Archive in the Sky,

to wander the Akashic Records even. It is now that I find myself looking around me in

my music room, at the filled shelves, nay, the crammed shelves, and I wonder, a la Cecil

Gant, I wonder: What the heck is going to happen to all of this?

The distressing reality is that my collection is not only eclectic, containing as it

does both common and obscure records, but it reflects tastes that, with the passing of

the years, are also passing. I have rock ’n’ roll records by the score, by the hundreds,

and ditto for R&B, blues, jazz, and country—all genres that have been very collectible

over the years, but whose fans and adherents are dying off, dying off by the score. And

my tastes have always been toward the obscure, the unknown, the folks that influenced

the influencers, the folks that most people have never heard of…the denizens of

obscurity, lost and dead voices, forgotten names lurking in forgotten times, those whose

records possibly never really sold much to begin with…and now, seventy or eighty or

ninety years on, who the hell knows about them? Very few, indeed, have the arcane

knowledge or, indeed, the curiosity to pierce those dense and dark veils of oblivion;

thus, the conclusion presents itself that the value of much of this huge and vast

collection, is therefore, well, not to put too fine a point upon it, inching close to zero.

And thus, I wander the shelves, pulling items and putting them on eBay, and if they

don’t sell, I transfer them to my website, 78crazy.com, and like the spider, await the fly.

I’ve sold a few dozen, some for some wonderful prices, others at a pittance, but the

music moves on, finds a new home, and a new collector has the chance, the

opportunity, to be entranced for the first time by a record that has served that very

purpose countless times for countless owners. Rooseveldt Graves and Brother, for

instance, on Melotone—their tune actually called “Woke Up This Morning,” the archetypical

opening line of a thousand blues songs—left the building this year, as did Blind Willie

Johnson on Vocalion. Dear old Willie…he and sweet-voiced Angeline, his wife, on a

cracked, yes, cracked yet still playable disc, attracted over two hundred views and over

one hundred watchers on eBay…irresistible gravel-voiced Willie, still pulling in the

crowds after all these decades.

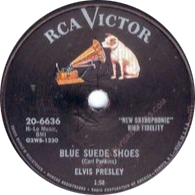

And Elvis, “Blue Suede Shoes” on RCA, sold for over $300 to my amazement—a great

record, but hardly rare, but someone out there had a great and yearning hunger for this

disc and happily opened his wallet. How about Len Spencer on American Record

Company, from 1901, with “Arkansas Traveler”? This one-sided blue shellac has a

beautiful label and a cackling string of hillbilly jokes that were probably ancient

when this was recorded, strung together by manic fiddle runs. Sample joke: “Where

does this road go?” “It don’t go nowhere—just stays right there!” followed by a wheeze

of laughter and wheeling fiddle, and on to the next superannuated jest.

From ancient black gospel to raunchy R&B, from WWI-era beginnings of jazz to

cool modern, from hillbilly church songs to western swing, from raggedy old blues to

sublime doo-wop, the discs slowly depart the shelves, wending their way back into the

world at large…sending out their messages of passion and despair, wonder and joy,

eccentricities and celebrations, rude folk primitif and art sublime. The collected tales and

lamentations of humanity expressed into ofttimes exquisite musical art, recorded in

studios, auditoriums, hotel rooms, radio stations or simply out “in the field.” All of them

mastered and pressed into shellac.

All of this brings me back to the swap at Down Home, and the wild, eclectic tastes of

those present that chilly morning: those who collected only jazz records from the ’20s

and early ’30s, the blues freaks who looked for Robert Lockwood, Jr. or Sunnyland Slim,

the beboppers who searched for Parker on Dial, or the solitary Hawaiian specialist who

looked for slack key recordings. A strange and motley assortment of collectors, mainly

men, and until recently, mainly older men—although it is true that a refreshingly younger

and mixed crowd has emerged over the last few years, which is necessary and

appropriate.

For these voices from the past speak to all of us who have followed, and to

those who will follow us. For these are the voices and sounds of humanity, frozen in

moments of time long passed, slumbering in the groove, awaiting the waking stylus.

*The day I finished this piece, my wife and I attended a celebration of the life of Chris

Strachwitz, who passed away on May 5th, 2023, aged 91. Chris founded Arhoolie

Records in 1960, and started Down Home Music, the revered record store in 1976. His

life was synonymous with blues, zydeco, and American music. It was the parking lot of

Down Home Music that hosted these 78 swaps and had done so for decades. Chris

was the perfect record man—one who loved the music and musicians, and the records

they made.

The personalized license plate on his car said it all—it read: “78s.”

Comments